Comanche Cellars Gives Us a Lesson in the Intensity of Wine Production

If you’ve ever been on our Old Monterey Food Tour, or tried out the Something Wild Mindful Food Tour, you’ll be familiar with our last tasting of the day — Comanche Cellars. As lovers of wine ourselves, we admit that we never thought too much about wine production, so when the owner of Comanche, Michael Simons, invited us to join him for this year’s bottling session, we had no idea what we were getting ourselves into.

As for Simons, what started as a passion project has now turned into a full-blown wine production center. He has a deep love for wine, and back in 2007, started attending a class at a wine shop on Carmel Rancho Boulevard. Although the shop itself is no longer around, the memories will be with him forever. The owner of the shop, Jacque Melac, and his wife Janet, a chef, held the weekly meetings with wine and food pairings. After attending every meeting, every week, for a couple of years, Michael joined up with a few of the others from the class to start making and tasting their own wines.

As he started perfecting his craft, his kids started asking him what he was going to name his wine label — something he hadn’t even thought about until questioned. They discussed the name Comanche, who was the horse Simons used on his paper route when he was a kid. When the son of one of his daughter’s friends gave him an oil painting of a wine bottle with the Comanche label on it as a Christmas present, he knew he had his moniker. Additionally, he created the Dog & Pony label under the Comanche main label, and named another wine, Maverick, after his dog that would join them on the paper route.

Apart from having fun and making wine as a passion project, Simons quickly learned that mass production is an entirely different beast. For example, when harvest season comes around in the fall, you have to have the macro bins — which hold half a ton of fruit — placed at all the different vineyards, ready to pick the grapes. Picking day itself has you out in the fields at 5 in the morning until anywhere from 11am-3pm. Clear, cool weather is perfect for slowly ripening fruit, but any spike in temperature has everyone scrambling to get the grapes to the winery. There’s bacteria and yeast and everything already on the fruit, so you want to be careful to keep the berries intact.

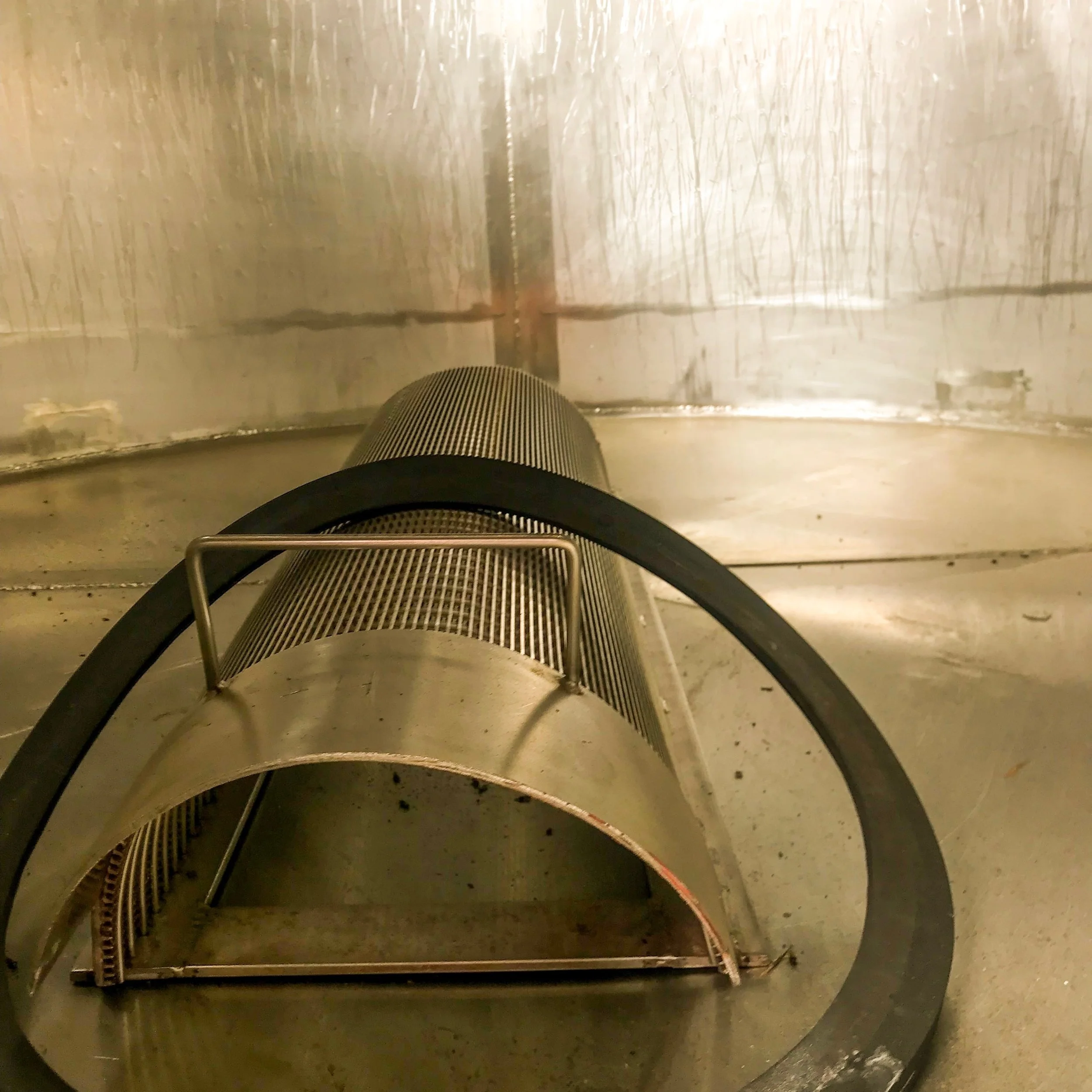

The destemmer

Once the picking is done for the day, you take the macro bins (which now hold more than a few tons of fruit) back to the warehouse, where they’re put through a destemmer. The fruit drops into a hopper, and the paddles connected knock the berries off the stems. The stems are spit out into a bin in the front, and the destemmed fruit that’s ready to start fermenting, drops into a bin below.

Just don’t forget to clean up all the equipment once that’s done, which makes picking day almost a full 24-hour process.

And that’s just the beginning.

“If you have a wine that’s harvested too early, the acids are too high,” says Simons. “When a grape is developing, the plant has a way of keeping the birds from eating them. Naturally, there are very high tannins, and very high acids. As the sugar accumulates, a process called veraison happens. All grapes are green at first, and veraison turns them red. As the sugars develop, the acids and tannins come down, and then you have a balance. There’s about 24-25% sugar in the grapes by the time they’re ready to be harvested, and grapes are the sweetest fruit in existence. Just as you don’t want too much acidity, you also don’t want too much sugar.”

A hydrometer is used as the juice ferments which checks the “brix” of sugar in the must. The sugar content of ripening fruit can change really fast, because if it gets hot, the water dehydrates, the sugars go sky high and so will the alcohol. Constantly checking the levels of the sugars, acids, and tannins is a must for making a good wine.

Once everything is picked, destemmed, and in the case of white wine, pressed, then it’s time for the yeast to come in and the alcohol to form. Once fermentation is completed, Sulfur dioxide, or S0 2 , is used to protect the wine. A sample of the wine goes into a titration system, and it’ll give a reading of the parts per million of the S0 2 currently in the wine. This is a process that has to be checked every few months throughout all of the barrels to make sure the wines are protected properly.

"Acids are also important, because besides volatile acidity, total acidity is important to know for the wine as well.”

Sound complicated yes? We haven’t even gotten to the most intense part, and the part we got to experience for ourselves — the bottling.

Our fearless leader, Casey, drenched in wine on bottling day

Although harvesting brings a lot of weight loss and stress, the bottling process is most commonly agreed by the winemakers as the most stressful part. On bottling day, everything has to be ready to go. You need the bottles, labels, the corks, the foils, and you have to be organized for all the different types of wine you’re about to bottle. The federal government has to issue a Certificate of Label Approval, or COLA, and it takes time to choose everything.

As for us, showing up on bottling day turned into quite the eye-opening experience. We walked into the warehouse, where a trailer that had an entire machine inside of it was parked right outside. The trailer has a hose that connects to the tanks that are now full of wine, and an assembly line is waiting inside the trailer. At the start of the line, there’s someone who dumps the box of empty bottles onto the line. The machine grabs each bottle, sparges them with nitrogen to replace the air, fills them, corks them, then spits them out into the middle of the trailer, where two people stand waiting to cap the foil on every bottle. After that, the bottles go through the other side of the machine, where the foil is pressed around the bottle head and the label is attached. At the end of the line, two people wait for every bottle to put back into the empty boxes, then send them down a chute where two other people wait to stack them on the pallets and get them ready for shipping.

The machine is set up to do 200 boxes per hour, and the day we bottled saw 13,000 bottles get ready for shipment.

Although the bottling is the most intense process, the best part comes when it’s done, because then, it’s done.

Everything from harvest to end product is very busy, and nothing Simons shared with me even begins to explain the differences between making a red and a white wine. As for the Comanche product, however, Simons says, “The nice thing about not owning a vineyard is that I’m not making the same wines all the time. Climate and soil has a lot to do with the wine and the flavor, so it’s good to be able to do what I want as far as making different wines from unique terroir.”

The vineyards Simons pairs with for the grapes harvested for Comanche go as far north as Mendocino county, as far east as the Sierra Nevadas, as far south as Paso Robles, and also with the Salinas Valley. As of now, there are 17 different varietals to choose from, but Simons loves experimentation.

When asked what the most important thing he has learned from owning his own winery is, Simons emphatically states, “Pay attention! Boy, you better pay attention to everything, or you’re going to get overwhelmed.”

As overwhelming and intense as the process is, however, there’s one thing that makes it all worth it in the end: The people who drink the wine.

“All of the hard work pays off when you see people enjoying the product you’ve worked your ass off for,” says Simons. “And for me, I wouldn’t be able to do anything with the tasting room or anything like that without my partner, Christina Cohen.”

Christina initially approached Simons with the idea of selling his wine in a more mass-production state, and Simons describes her as a real force when it comes to getting the product out there. They decided to open up the tasting room, which has just celebrated a year of business on its own, and she’s an essential member of their team who understands that the process of making wine doesn’t end when it goes in the bottle — it ends when the people enjoying it empty it out.